|

Ordnance Survey

Maps - The best maps for walking in the UK

See the full range of

1:25000 Ordnance

Survey maps .

It is fairly

safe to say that "OS" maps are the best in the world giving a

wealth of information in a variety of scales. The most familiar are the

1:50,000 Landranger and 1:25,000 Explorer ranges. They are available from

most walking shops, many tourist shops and direct from Ordnance Survey. Amazon also sell them

often at

reduced cost and have a very efficient delivery.

A direct link to buy the map specific

to each walk, described under My Walks, is given on the

appropriate walk page. For walking, the 1:25000 series are strongly

recommended as they show far more detail to help you navigate, not least

field boundaries which are very useful for monitoring your progress across

the countryside or working out exactly where you are.

The

best way to look after maps when walking is to use a proper map case. This

needs to be waterproof and after trying various kinds over the years, I

recently (2021) purchased the Aquapac Kaituna Waterproof Map Holder.

It is slightly larger than my previous ones, which makes it easier to get

the maps into it. It is genuinely waterproof and I think my OS maps are worth looking

after.

Alternatively,

you could scan/print out a map on waterproof paper.

|

This paper scores very

highly in Amazon's Customer Reviews

Waterproof and suitable for

outdoor use, Tough and resists tears

Durable and wipe clean. High defenition and vibrant colours

Click the image for more

information

|

About Ordnance Survey Maps

The history of

the Ordnance Survey began in 1791 when the Government directed its Board of Ordnance,

the early equivalent of the Ministry of Defence, to survey

the south coast of England so that it could be adequately defended from

invasion.

So

"Ordnance Survey" (OS) was born and went on to comprehensively map

the entire country.

Thousands of

triangulation stations were set up at high points around the country from

which measurements were taken. These are the familiar Triangulation Pillars

or "trig

points" which walkers see on their travels. An example is shown below.

Use of these has

been superceded by the use of satellite and laser technology but the trig

points themselves are a very useful navigational aid for walkers as they

confirm your position on the ground.

They are designated on the 1:25,000

scale maps by the symbol below:

If you want to know more about

the history of the Ordnance Survey and indeed about the history of maps in

general, I enthusiastically recommend the book On The Map by Simon Garfield.

This covers the history of maps from early sketches several hundred years BC,

to Google Earth. I genuinely could not put it down.

Some

straightforward walks can be done using the 1:50,000 maps but the larger

scale 1:25,000 are much more detailed with a greater number of paths and

geographical features. This is the scale you should use and the one on which

we will concentrate.

On the 1:25,000

maps, 4 centimetres = 1 kilometre. (2.5 inches = 1 mile). For a quick visual

reference, the smaller 1 kilometre grid squares are a mile corner to corner.

To explain the

logic of the maps (and please bear with this), Great Britain is covered by 4

large 500 kilometer x 500 kilometer squares each assigned a letter H, N, S

and T.

These are each

then sub-divided into twenty five, 100 kilometer squares each of

which has another letter from A to Z (excluding I). So, if you take the

Explorer Map for The North Eastern English Lake District, its top left hand corner contains

the letters NY, the N representing the relevant 500 km square and the Y the

relevant 100 KM square.

These are

further broken down into 10 km x 10 km squares which are allocated a number

0 to 9 working from the South West corner of each 10km square, north and

east.

A further

sub-division breaks each 10 km square into 1 km squares and these form the

blue grid you see on an OS map and identified by the blue numbers across the

top/bottom and left/right hand sides. The numbers are also shown at

intervals across the maps for ease of reference in use.

Of course even a

1 km division is not sufficient for accurate navigation so this square is

divided yet again by an imaginary grid working in 10ths. A full OS reference

number for the summit of Helvellyn in the English Lake District would be:

NY 34170 15160. To break this

down and explain:

NY

34170

15160

-

N = the 500

km square

-

Y = the 100

km square

-

3 = the

number of the 10 km square

-

4 = the

start of the 4th 1 km square of that 10 km square working east

-

1 = the

number of 10ths across that 1 km square working east

-

70 = 0.70 of

that 10th

The 15160 works

on exactly the same basis but working northwards.

A simpler way of

thinking about it is that in effect the 100 km square is broken into 100ths

and the numbers from 00 to 99 are the numbers you see in blue marking the

blue grid lines on the 1:25,000 maps. Each square is 1 km x 1 km.

The

"34170" is called the "easting" and the

"15160" the "northing". OS references always give the two letters, the "easting" first, then the "northing"

In practical

terms, because it is quite difficult to accurately assess manually on a map

to six figures in each direction, OS references usually stop after 3 figures on each bearing

thus the reference above would be NY 342 152 or NY342152 (rounded up).

To demonstrate

this graphically, see the image on the right. The trig point is always displayed as a

triangle on OS maps so if we imagine the image to be the NY section

of the country, the trig point is at position NY 34170 15160. The dotted lines

represent the imaginary 1/10 divisions of the 1 km square. The bracketed

entries are the high precision elements we would not usually quote.

OS maps give the

two letter coding at the corners and again if it changes part way across a

map, if the map overlaps two grid letter areas.

The OS Grid

References are actually of little practical value in actually finding your way (except

in relation to using GPS machines). They can be invaluable in an emergency

however in directing rescuers to a specific point, assuming you know exactly

where you are.

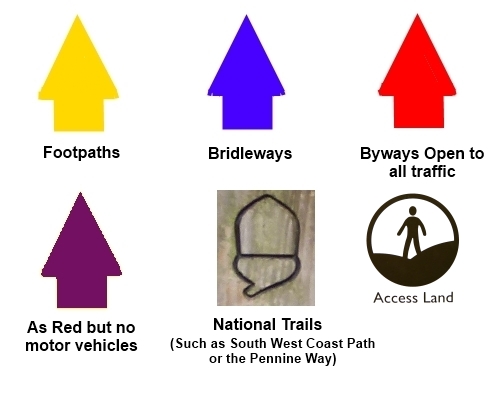

All OS maps have

a detailed key which explains all the symbols. The ones of most significance

to walkers are of course the footpaths shown below..

There are a

number of other paths/tracks marked on maps which may or may not be accessible

to the public. Those on open country usually are but some could

be private drives. This is one area where taking walks from books means

someone has done the groundwork for you.

In the field, route indicators

often bear signs which relate to the symbols on the OS maps as follows:

A

full list of OS map symbols can be viewed on the Ordnance

Survey website. Other

important indicators on the map are the brown contour lines which follow the

elevation and are at 10 metre vertical intervals and the patchwork of thin

black lines which indicate field boundary walls. Walls and rivers/streams

can all help you to relate the map to the terrain around you. The

contour lines enable you to judge the severity of the terrain and can help

judge the timing of walks (See the section on Safety). The closer together

the lines are, the steeper the gradient. The

field lines, by indicating the shape of fields will help you to work out

your position as will indications of other features (e.g. farms, churches,

barn, streams etc etc). One

of the difficulties walkers have with map reading, especially if trying to

follow a walk from a book, is that the map only sees daylight once they

become "lost". It is actually sometimes quite difficult to relate

the land you see around you to what is shown on the map if there are no clearly

distinguishing features. If however you have plotted your course first and

then referred regularly to the map during the walk, you will always have a

pretty good idea where you are eg. the footpath going over a marked

footbridge, passing through a wall, past a barn or a farm etc. Do

not be lulled into a false sense of security by thinking because you have

seen a clearly marked signpost (eg. 3 miles to village x) or a bright yellow

blob on a farm wall that there will necessarily be another equivalent marker

when the path becomes indistinct on the fell or even changes to another

landowner's property. In the UK, we seem to have a

bad habit of only doing half a job on footpath marking! This

can also be a time when use of the compass comes into its own. However to be

effective in route finding, you need to know where you are when you use it.

Although it is theoretically possible to establish your location by using

the compass, this assumes that you can clearly identify some landmarks. This

is not always so straightforward.

Using

a Map and Compass Reading List

All information on this

site is given in good faith and no liability is accepted in respect of any

damage, loss or injury which might result from acting on it.

|